High disposable income made young baby boomers very attractive to marketers. Today, many young people are struggling to find work and future spending power is shifting to the older generations.

Disposable income was what originally made young baby boomers so attractive to advertisers. Historically, young people worked – either on holiday or direct from school – unlike unpaid internships today. With little reason to save and no dependants or responsibilities, they were a

marketer’s dream. Today, significant paid work for young people is a thing of the past. In 2016 just 43% of American 16- to 19-year-olds were working in July, during the summer holidays—down from 65% two decades earlier. Teenagers now have other priorities. Thanks to the minimum wage in many markets, pay has improved from previous years but it is still a pittance next to the cost of university tuition or the large and growing wage differential between professional-level jobs and the rest.

The young are eschewing income and frivolous spending today, instead investing their time in studying while taking on debt to pay for increasingly costly education.”

The drop in summer working has been mirrored by a rise in summer studying and internships. More teens attend school during the summer now than in previous years. The proportion of teenagers enrolled in July 2016 was more than four times higher than it was in July 1985—42.1% versus 10.4%. Today, teenagers and young people around the world are more focused on academic work and job readiness. Across the OECD club of rich countries, the share of 25- to 34-yearolds with a tertiary degree rose from 26% to 43% between 2000 and 2016. This, combined with the increasing cost of further education, means that the young are eschewing income and frivolous spending today, instead investing their time in studying while taking on debt to pay for increasingly costly education.

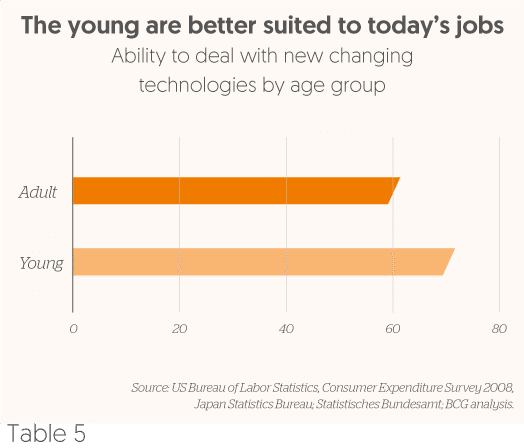

Thanks to better education and improved nutrition, intelligence tests show that younger generations are brainier than previous ones – especially in the much sought-after areas of problem solving. Yet this does not translate into better job opportunities.

In most regions, millennials are twice as likely as their elders to be unemployed. Not only is the job market more competitive than ever, in many countries employment rules favour those who already have a job. Rigid labour laws in many developed markets are tougher on younger workers. People without much experience find it harder to demonstrate that they are worth employing, and when a company knows they cannot easily get rid of poor performers, they become reluctant to hire.

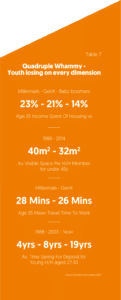

The housing market also works against the young – compared to previous generations – on four levels: the higher cost of rent as a proportion of disposable income, the smaller sizes of affordable accommodation, the lengthening commute to affordable areas, and the huge increase in the time needed to save for a deposit on a mortgage (see table 7)

Constraints in the supply of housing in mega-cities where many of the good jobs are located exacerbate these factors, reducing disposable income and the time and space to enjoy it. And it doesn’t end there. Unlike baby boomers with fixed salary pensions, or gen Xers with safe jobs and valuable property, these younger generations will need to save more to fund the cost of their 100-year-life. To make matters worse, in rich countries, public spending favours pensions and healthcare for the old over education for the young, paid for by borrowing today

which the young will have to pay for tomorrow.

Sadly, younger generations are not doing all they can to help themselves; typically voter turnout around the world is nearly half among 18-24s compared to the over-65s.

It is therefore no surprise that young Brits are experiencing the tightest squeeze on household spending since 2000 and now consume 15% less than older workers on items other than housing (source: Resolution UK, 2017). This finding of a consumption ‘youth deficit’ is in stark contrast to common media claims and marketing perceptions that today’s young are spending like there’s no tomorrow. The strongest future growth potential in spending however lies not in these older workers but in older people in general.

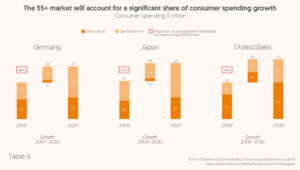

In less than five years, 50% of the US population will be over 50. Not only that, but they will control 70% of the nation’s income and stand to inherit $15 trillion in the next 20 years. Yet for most brand marketers, the over 45s are not seen as having any growth potential. It might surprise them to know that in the 1970s, baby boomers were the first twentysomethings, nicknamed the ‘me generation’ as they intended to spend their money on themselves. Consumption amongst those aged 60 and over rose 50% compared to those under 30 over the past two decades, according to Eurostat. In the coming years, over 55s are expect to represent 50-86% of consumer spending growth (see table 6).

This generation of empty nesters is rediscovering the joys of youth while those who never had kids are still indulging. Americans over 60 are divorcing at twice the rate as in 1990, and in UK it is three times. In the US, 55-64 year-olds are 65% more likely to set up a business than 20-34s (Kauffman Foundation). We expect these major life events to translate into changes in brand behaviour. After all, the over-50s represent 40% of adventure travellers (Adventure Travel Trade Association). Behaviours like these suggest that many are looking for something different.

This does not mean that we should be targeting baby boomers exclusively despite their increasing prosperity. In the world of addressable advertising we should be ‘age-blind’ and take a perennial approach. If we want to target disposable income, we should be looking at targeting people with the income, brand inclination, time and space to enjoy the experience, irrespective of age, gender or any other outdated targeting label.